When the Father, and the World, Wore Sackloth

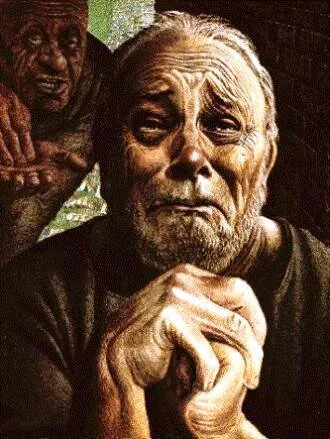

Grief is a wandering through catacombs. Shadowy, unearthly, and lacking in that ordinary wheel of human existence: a goal. Aimless because there is no clear goal in grief, the mourner meanders. Plodding deeper into the darkness seems the only direction, if it can be called direction. In the biblical world, grief, that amorphous back-and-forth of protest and wailing, that subterranean pilgrimage cut off from light, has a wardrobe: sackcloth. And there was a time God wore sackloth, and the whole world too.

Sackloth was an ordinary goat- or camel-hair sack worn in times of mourning or protest. When made of goat hair, it was black in color, and was worn when the mourner wished to publicize his or her sorrow. It was thus an invitation to share that sorrow as well as to object to the world that makes it possible. This facet of sackcloth is significant rather than peripheral to biblical grief: the garb of grief declares that death or sin has disrupted the orderliness of the world and needs to be put right (2 Sam. 21:10; Esther 4:1; Daniel 9:3; et al.). Rizpah used it to protest Saul's improper burial (2 Sam. 21) and in response David ordered a fix. Several OT kings and captives wore sackcloth in order to plea for mercy or in fear of an imminent threat. Of course we are most familiar with sackcloth in connection with repentance: as God approaches in judgment, one should wear sackcloth (Isa. 3:24; et al.).

The connection of sackcloth with darkness has a deep biblical pedigree. In a foretaste of Golgotha, Isaiah 50:3 reads "I clothe the heavens with blackness and make sackcloth their covering;" and in a symbolically rich retelling of that moment at the Skull, Revelation 6:12 reads, "When he opened the sixth seal, I looked, and behold, there was a great earthquake, and the sun became black as sackcloth."

In all this I am of course prodding us to reconsider what Matthew tells us, "Now from the sixth hour there was darkness over all the land until the ninth hour. And about the ninth hour Jesus cried out with a loud voice, saying, 'Eli, Eli, lema sabachthani?' that is, 'My God, my God, why have you forsaken me?' (Matt. 27:45-46). We are accustomed to reading the darkness of the cross in terms of the judgment the Son endured in the place of sinners, the curse of exile and the absence of divine favor that belonged properly to covenant-breaking Israel. In my view, despite ongoing objections out there to the notion, this is not only difficult to deny biblically but essential to the significance of the cross in the biblical world. It is at the heart of the wide-ranging biblical reality we should intend in our confession that he "descended into Hell," again in my view.

But is it possible that judgment on and in the Son is not the whole picture? That the Father also mourns the Son? We have an important anticipation of this in the book of Lamentations. In the regular ways in which Lady Zion's suffering is both clearly deserved as judgment and at the same time, even to the same degree, recounted in order to elicit deep sympathy with her plight, we discover one (deserved judgment) does not cancel out the other (sympathy with horrible suffering), and the occasional notes in Lamentations of the suffering being undeserved in some respects creates space for a third dimension for the crucified Jerusalem at Golgotha: injustice. Instead of choosing one of these to the exclusion of the others, we are drawn to the darkness of Golgotha as the time God spread a cloak of darkness, or sackloth, over the world, both as a protest of the injustice of the Son's death and as deep mourning over his Beloved. In the ultimately inscrutable mysteries of what happened in the darkness at the cross, the Father, I suggest, donned sackloth - and, as in Matthew, pulled the whole world under the cloak of it - not instead of acting in judgment for sin upon the One Who became sin there, but alongside it and with it. We know the voice of Rachel weeping for her children. Do we remember the voice of David mourning for his Absalom? "O Absalom, my son, my son!" (2 Sam. 18:33). Would the Father of the Son mourn less than his servant, David? And wouldn't the eighth day of luminous resurrection become, then, the dawn of justice realized and the eternal day figure the robes of endless rejoicing?

*For further study, include in your research the following insightful articles: Yitzhak Berger, "On Patterning in the Book of Samuel: 'News of Death' and the Kingship of David," JSOT 35.4 (2011): 463-81; and J. Gerald Janzen, "The Root skl and the Soul Bereaved in Psalm 35," JSOT 65 (1995): 55-69.

*Also, if you have never heard Eric Whitacre's "When David Heard," do yourself a favor and carve out fifteen minutes to do so. (My thanks to Jonathan Stark for pointing me to this.)